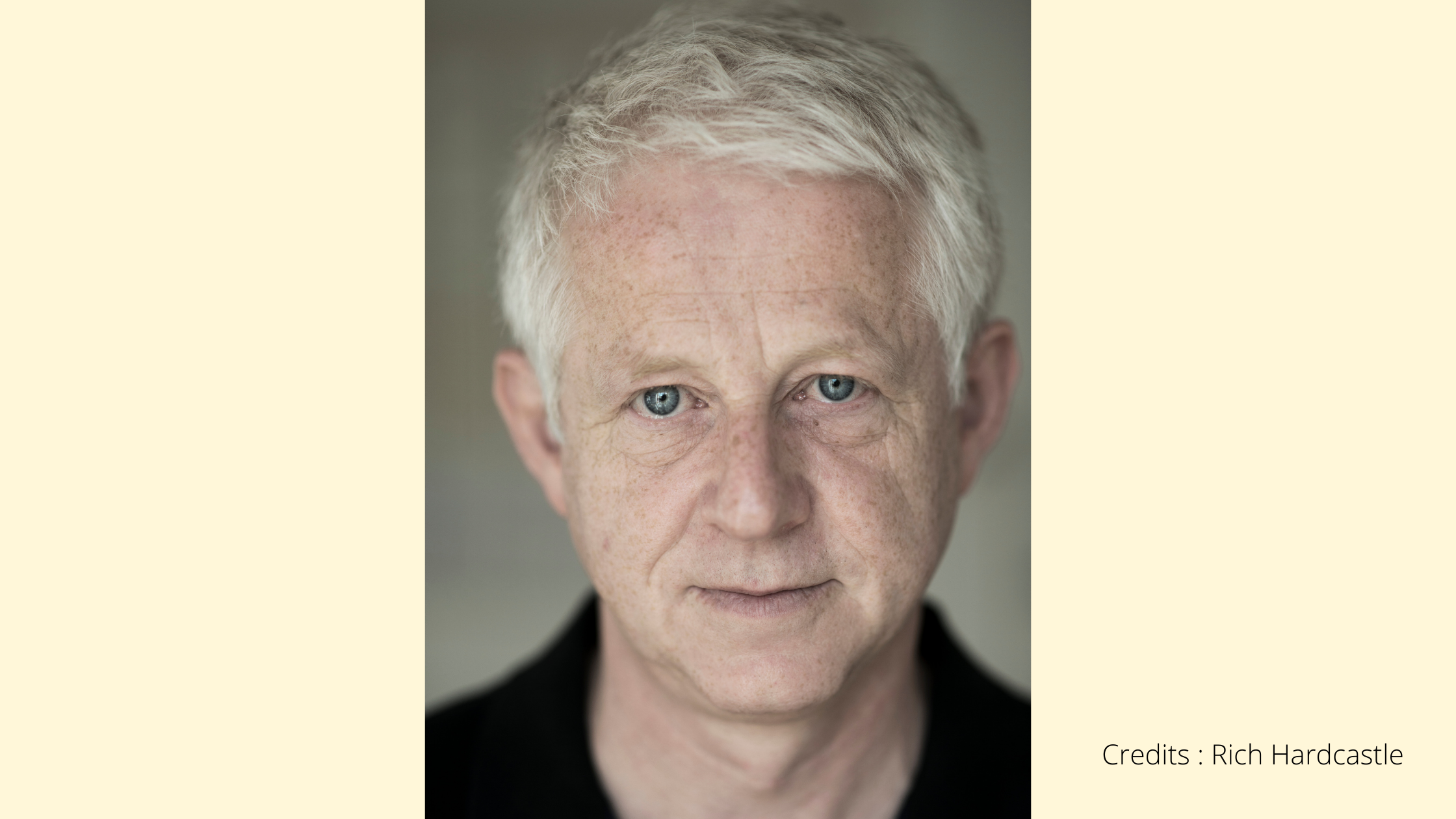

Richard Curtis : Love, Humour &… Action !

Famous for being the unrivalled master of the ‘Brit rom com movies’ since 1994 with Four Weddings and a Funeral, Richard Curtis is also a great ambassador of charities and the founder of Comic Relief and Red Nose Day since the 1980s. It is from Los Angeles where Richard Curtis recently relocated with his family, that he very kindly accepted this interview on Zoom.

Who was the young Richard and what were his secret aspirations ?

When I was 14 years old, I tried to think of what I could be good at. (Laughs) I started writing funny articles for the school magazine and acting in plays. Which led me to think maybe later on I would do something related to writing or acting.

Could you share a memory of your first writing moment?

For me it was always very satisfying when I wrote something funny.

Looking back, I think it was very useful to start with journalism. In a way my journey started with writing comedy articles for a school magazine, then sketches, then comedy situations for TV and eventually writing for films. As a young editor of the magazine, I realised very quickly that you had to start with a clear idea and develop it a little bit more each time with a comedy angle, trying to make each subsequent joke funnier and funnier.

I think I’m an old-fashioned example of someone who learned his craft the hard way. Some young people today think that I started writing films straight away, but in fact I had a long journey to get there.

How did you start as a writer?

I first wrote one or two things for a television show that ended up being quite successful, although I wasn’t really responsible for that at all. (Laughs). It was for a sort of satirical show called Not the 9 o’clock news and I was part of a team where there were lots of writers!

Then I was involved in writing a kind of big concept comic-historical show called Blackadder. In both of these projects, there were only jokes and no emotion at all.

And later on (after the Mr Bean adventure, among others, ed.), when I decided that I was going to write films, it was mainly with the idea of writing about feelings like romance and friendship.

There were also some films that inspired me a lot such as Breaking away, Gregory’s girl or Woody Allen’s films.

You met Rowan Atkinson at Oxford. What did you learn from each other ?

Well, it’s an interesting point because when I first met Rowan I was trying to be funny myself, doing sketches at college. And at only 19 years old, Rowan was already acting completely brilliantly like Charlie Chaplin.

The first thing I learned from Rowan was to focus first and foremost on my writing. With Rowan, I learned to be ready at any time to rewrite a sketch and so, in a way, he helped me develop my own sense of perfectionism and rhythm!

A funny point is that your first film as a writer, The Tall Guy, puts the spolight on the duo formed by Rowan Atkinson, an obnoxious and famous comedian and his martyred and invisible partner on stage, in fact the hero of the film, played by Jeff Godblum…

It’s a very satirical writing of my working relationship with Rowan which is at the heart of the film obviously! (Laughs). I admit I haven’t seen the film for 30 years but I think it was a good trial run, even if it was perhaps a little bit insincere. A bit too funny « at all costs », as in my previous work, a bit too cartoonish too.

The big change in my life came when I found a serious director to direct my films seriously, with more substance but still keeping the gags I had concocted. I also think that the choice of actors in the next film was very important. I’m not talking about Emma’s acting or Jeff’s acting, of course, but in Four Weddings we took a lot more time to choose our actors.

« When you’ve found the right cast, three quarters of the film is done. »

How did your collaboration with Working Title start?

Since my first film The Tall Guy! To tell you the truth, I think that working with them takes 40% of my problems out of making a film. They’ve given me a kind of discipline, freedom and support that is invaluable and keeps me from getting notes from lots of different people I don’t know. A real « creative marriage », in a way! (Laughs).

On Four Weddings, how did the casting go?

What I learned above all was that you have to dedicate a lot of time for the casting. Hugh was the seventieth person we auditioned and until we met him, no one said the lines in a funny way. After I met Rowan, my meeting Hugh was a new turning point in my career. For this part, we had met everyone in the business, and the process was almost as long for the other parts. Which illustrates the saying about a film « once you’ve found the right cast, three quarters of the film is done »

Unlike 4 Weddings, you wrote Notting Hill with the perspective of writing a ‘Brit-rom-com’ …

You’re absolutely right. When I wrote 4 Weddings, I didn’t think of it as a romantic comedy but more as an autobiographical film with love as its main subject.

For Notting Hill, I had this very simple idea of highlighting a big problem about love and fame. But it’s a very long process to write a romance: you have to be sincere about your own vision of love and see how it can work properly.

So there was an early version of the film already complete where Hugh met Julia but also another girl, who lived on his street. He had to choose between the two. And in fact he chose the other girl. But deep down, that idea broke my heart.

Basically, you have to focus on : what you think is most moving, most romantic and fun to tell.

What do you think about the different methods and writing structures proposed by John Truby or Robert McKee for instance ? Do you have a specific method you use ?

I personally think they are dangerous. When you get to a certain point in the film, you should write what you think is right and follow your instinct. It scares me when you are told that at this point things have to happen like this, with a new character on page X…

You’re following a roadmap and you might make a bad decision.

For me, the really interesting script I read was The Graduate. It’s such a strange form of storytelling. The first night between Anne Bancroft and Dustin Hoffman only happens on the thirtieth page! Not following the rules sort of makes me feel better. (Laughs).

« When I write small parts, I often give them each ten pages of dialogue. »

With Love Actually in 2003, you took a new step in your career: you directed a movie !

At that time, I didn’t really want to write any more whole romantic comedies and obviously, I ended up writing a film based on a lot of romantic plots. (Laughs).

Hugh Grant’s and Colin Firth’s were planned for two whole films respectively. As I was a huge fan of choral films such as Nashville, Short Cuts, Smoke and Pulp Fiction, I thought then I’d do this as a romantic comedy.

And the reason for directing this film myself was that I was becoming more and more opinionated about how to shoot a film. Even though my knowledge from a visual point of view might not look as good, I was confident I could use the lessons learnt from the directors I had worked with.

When you are directing, there is in all your films a very special ingredient with which you play, like a kind of second language, namely music.

Indeed, sometimes I wonder if my career hasn’t been entirely hijacked by music (laughs) because I wrote two films that were totally dedicated to music. As I often say, the real love of my life is pop music, not films. (Laughs)

How do you work the music in your films?

First of all, when I write, I listen to music. It artificially puts me in a good mood and that’s how I start my writing process.

There are two songs in particular in Notting Hill that I listened to all the time when I was writing: ‘Downtown Train’ by Everything But The Girl and the other is called ‘Wastin’ Time’ by Ron Sexmith.

During filming, any piece of music found while writing the script will also really help you like ‘All by myself’ in Bridget Jones or ‘All I want for Xmas is you’ in Love Actually…

When editing (my favourite part of making a film), I can also use a piece of music as inspiration to find the right emotion for the scene. For example, there was a scene in Love Actually where during the editing process we used George Michael’s version of ‘The first time ever I saw your face’. But eventually it wasn’t in the film because we decided to use score and not a song.

And in About Time there were some really important pieces of music like ‘The Luckiest’ by Ben Folds, ‘Gold in Them Hills’ by Ron Sexsmith.

It was sometimes as if this conversation with the music I was having, was helping me to write and make the films.

In The Boat that Rocked, as in most of your films, there is a great importance given to the secondary characters. How do you work with them?

Yes, you really have to focus on your secondary characters. Mike Newell said this brilliant thing to me when we were doing Four Weddings: « when you finish writing a film, you have to reread it as many times as the number of characters you’ve created, pretending that you’re the actor who’s going to play their part for each one. »

So you have to be sure that the role has a beginning, a middle and an end.

The second thing is to find their own voice. When I’m writing small roles, I’ll often give them each ten pages of dialogue where I just want to try and understand how they speak, not how they’re useful. And I think that really helps.

And again, the choice of the actor who is going to give the character his or her human dimension really matters.

The director Roger Michell who worked with you on Notting Hill recently died. Here, as a tribute to him, can you tell us what you learned from him in a way?

I learnt a lot from him and in particular in his love for actors and his ability to bring out the best in them and in particular to know how to listen their own propositions.

For instance the character of Bridget Jones with Renée Zellweger. When we were editing the film at the beginning, we were focussing on the voice-over in order to respect, as much as possible, the spirit of the book. One day, I sat down and realised how Renée’s performance was different but how she offered a wonderful Bridget.

There is another side of your personality that the public is less aware of and that is your social commitment. This is the subject of The Girl in the café (2005), a romantic comedy as well.

Yes, I wrote it when I was involved in the ‘Make poverty history’ campaign, which also included the Live 8 concert and of which I was one of the producers. I tried to write an activist film by combining it with what I knew the best, which was writing romance.

My deep interest in social issues has not been sufficiently reflected in my films so far, but it really represents my other life. I also wrote Mary and Martha, my film about malaria, with this in mind.

In conclusion, what three words could best define you?

I would say ‘optimistic, funny and committed’.

First, ‘optimistic’ because I think that when you’ve been lucky enough to have a life as happy as mine, you might as well write about it rather than about death or trauma.

‘Funny’ in the sense of ‘making people laugh’, which is also very important to me, in my life and in my work.

And finally ‘committed’, dealing with my deep interest in social issues which has not been sufficiently reflected in my screen work so far, but which concerns really my second life**.

*American screenwriting consultants and professors John Truby and Robert Mc Kee have each written books on screenwriting and romantic comedy writing. **Richard Curtis is also the founder of several major British charities: Comic Relief (created in 1985) Red Nose Day (1986), Make Poverty History (2005). My special thanks to Richard Curtis, his team and Rosalie Carn (for the translation's collaboration).